The Correlation Between Drug Half-Life and Addiction Treatment Medicines

Written by The Orlando Recovery Center

“How does this drug really work?” That’s not a question most people who take drugs ask before they dive in, but it is an important concept to understand. After all, a drug’s vital composition just might hold the details an addicted person needs to know in order to recover.

A drug’s half-life is one such detail. This one metric can help people to understand both why the drug they’re using seems hard to quit, and that detail can help people to work with their doctors to pull together treatment plans that can help.

Formal Definitions

Drugs work by coursing through the body’s tissues, triggering chemical and electrical changes as they go. The body works to counteract those changes by digesting the drug, utilizing the drug, or otherwise rendering the active parts of the substance inactive. When all of that work is done, the drug no longer works.

It’s a complicated process, and researchers typically condense the long-winded theory into one term: half-life. This term, experts say, represents the time it takes for the body to remove half of the drug.[1]

A drug’s half-life is an important metric for medical professionals who prescribe the drug to patients. By using this number, they can determine how much of a drug to give to someone, and how often the drug should be taken. But, unfortunately, determining a drug’s half-life can be an inexact science.

Researchers point out that some drugs have so-called “known” half-lives based on studies performed decades ago, but when newer research is conducted, some drugs seem to have either shorter or longer half-lives.[2] Some researchers have become so concerned by this idea that they’ve performed long, detailed mathematical calculations about how much of a drug is available in the bloodstream at specific points in time.

Even then, the half-life a person can experience can vary dramatically from the mathematical models. Some people are tall, while others are short. Some people are thin, while others are not. Some people have perfect organ function, while others have scar tissue. All of that could impact a drug’s half-life. In one study of the issue, for example, researchers suggested that the margin of half-life error for cocaine was more than four hours.[4] That’s a huge variability, and it demonstrates just how much a half-life might move from one person to the next.

While half-life might be a somewhat inexact number, it’s still vital for people who take drugs. For them, a half-life is a measure of the speed at which the drug clears the body. Those with longer half-lives stick around longer, and that could make a big difference, in terms of recovery. Half-lives can vary dramatically between drugs in the same class.

Good Examples

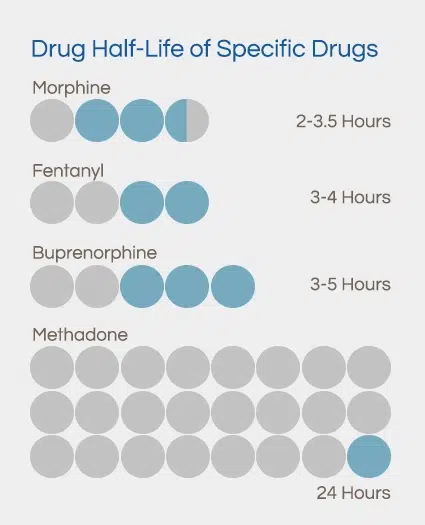

For a person who takes prescription painkillers, all drugs in that class could seem very similar, but there are dramatic differences between these drugs. These are half-life readings for just a few different opioid drugs: Consider putting these into graph form.

- Morphine: 2-3.5 hours

- Fentanyl: 3-4 hours

- Buprenorphine: 3-5 hours

- Methadone: 24 hours[5]

Clearly, even though all these drugs are in the same general class, they all have very different half-life readings. This kind of variability isn’t unique to the opioid class of drugs. Other drug classes also have a great deal of variation.

Benzodiazepines, for example, come in many different half-lives. In fact, they can be split into different classes, based on half-life: A chart or a table could be a good way to display this information.

- Short: Xanax, Ativan, Halcion

- Long: Librium, Valium, Dalmane[6]

What Does It Mean?

Drugs with different half-life scores are designed to do different things. For example, researchers say that drugs with a short half-life are designed for fast action. They’re made to hit the body quickly, so they can provide relief with speed.[7] Long-acting drugs tend to maintain their effects for a longer period of time, though the first dose takes longer to take effect.

That might explain why doctors are fond of prescribing long-acting drugs for people with medical conditions. Since the drugs work better long-term, people may get more effective relief. In a study of the issue, researchers found that 56 percent of prescriptions from primary care physicians were for long-acting drugs for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and 64 percent of prescriptions from psychiatric physicians were the same.[8] These doctors want long-term results, and drugs with a long half-life provide that relief.

Due to their quick effect, drugs with short half-lives tend to be popular with people who have addictions, researchers say, because they tend to deliver huge psychiatric changes in a very short time period.[9] For drug users who want a big high in a hurry, these medications seem to be tailor-made.These withdrawal symptoms can be so severe that they draw people back into addiction. In fact, in a study of the issue, researchers found that high ratings of withdrawal discomfort “contributed substantially” to the risk of relapse in people addicted to tobacco and cannabis.[11] People who feel ill are desperate for relief, and they might get that release by going back to drugs.

While researchers report that drugs with a short half-life don’t necessarily come with bigger withdrawal symptoms, many addictive drugs do cause changes that can be distressing when people attempt to get sober.[10] Those who try to quit might feel:

- Nauseated

- Depressed

- Anxious

- Restless

- Sweaty

- Twitchy

- Frightened

Get Personalized Addiction Treatment in Orlando

Orlando Recovery Center offers drug and alcohol addiction treatment personalized to fit your individual needs. Join the 50,000 lives who have trusted us with their recovery. Call us to find the right treatment plan for you.

Addiction Implications

If withdrawal discomfort can lead right back to drug use, it’s imperative that an addiction treatment program soothe discomfort. Often, the best way to provide relief is to provide people accustomed to short-half-life drugs with medications in the same class that have a longer half-life.

For example, alcohol is a sedating drug with a very short half-life. Chronic users who attempt to withdraw may experience a variety of life-threatening symptoms, including seizures. Switching addicted people to a long half-life, sedating drug can help the brain to adjust to the lack of drugs without plunging the person into a state of medical emergency. Doing so can keep people safe, and it can reduce the likelihood that they’ll self-medicate with alcohol.

Research suggests that benzodiazepines are some of the most effective medication therapies for alcohol withdrawal.[12] Many benzos have a long half-life, and they work on the same depressive circuits that alcohol does.

Similarly, people accustomed to heroin might be provided with methadone, which has a very long half-life.[13] It can soothe withdrawal distress, without providing the fast rush of heroin.

People who take benzodiazepines might also make a medication switch. Those accustomed to short half-life drugs might feel intense relief when they’re pushed to other options that have a longer half-life.

Simply switching drugs isn’t always enough to truly combat an addiction, of course, as people who take drugs often need a great deal of additional help in order to keep from using and abusing drugs over the long-term. Often, the recovery starts by switching drugs, and then tapering the dose.

The switch helps people to avoid the rush and the high, and the taper allows people to take smaller and smaller amounts of the drug, until they’re taking no drug at all. A taper like this can take a long time to complete. In one study of the issue, 45.2 percent of people taking benzodiazepines achieved sobriety only after a year of counseling and tapering. About 20 percent could only reduce their dose by 50 percent during that time period with the same kind of help.[14]

Not all tapers are this difficult, of course, and it’s quite possible that some people who take drugs could get better much quicker. It’s important to note that a tapering schedule can be lengthy, but it might be the best way to ensure a long-term recovery.

Not a DIY Affair

People reading through this information might be empowered to simply switch drugs and start tapering right now. Unfortunately, that’s not a good idea. Many drugs of abuse cause very serious withdrawal side effects, as mentioned, so it’s best to undergo a taper with the help of a medical professional.

If you are inspired to quit using drugs after reading this data, please consider getting help. With the right care, and the right supervision, you can beat your addiction and live the life you’ve always wanted.

Sources

Kramer, T. (2003). “Side Effects and Therapeutic Effects.” Medscape. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Sahin, S.; Benet, L. (Dec. 25, 2008). “The Operational Multiple Dosing Half-Lif[…]Release Dosage Forms.” Pharmaceutical Research. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Jufer, R.A.; Wstadik, A.; Walsh, S.L.; Levine, B.S.; Cone, E.J. (Oct. 24, 2000). “Elimination of Cocaine and Metabolites i[…] to Human Volunteers.” Journal of Analytical Toxicology. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Trescot, A.; Datta, S.; Lee, M.; Hansen, H. (2008). “Opioid Pharmacology.” Pain Physician. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Longo, L.; Johnson, B. (April 1, 2000). “Addiction: Part I. Benzodiazepines — S[…]isk and Alternatives.” American Family Physician. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

“Benzodiazepines Drug Profile.” (n.d.). European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Cascade, E.; Kalali, A.; Weisler, R. (Aug. 5, 2008). “Short-Acting Versus Long-Acting Medicati[…]he Treatment of ADHD.” Psychiatry MMC. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Longo, L.; Johnson, B. (April 1, 2000). “Addiction: Part I. Benzodiazepines — S[…]isk and Alternatives.” American Family Physician. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Kotzalidis, G.; Patrizi, B.; Caltagirone, S.; Koukopoulos, A.; Savoja, V.; Ruberto, G.; Tatarellli, C.; Pacchiarotti, I.; Lazanio, S.; Sani, G.; Manfredi, G.; dePisa, E.; Tatarelli, R.; Girardi, P. (2007). “The Adult SSRI/SNRI Withdrawal Syndrome:[…]Heterogeneous Entity.” Clinical Neuropsychiatry. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Budney, A.; Vandrey, R.; Hughes, J.; Thostenson, J.; Bursac, Z. (Dec. 2008). “Comparison of Cannabis and Tobacco Withd[…]tribution to Relapse.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Amato, L.; Minozzi, S.; Davoli, M. (June 15, 2011). “Efficacy and Safety of Pharmacological I[…] Withdrawal Syndrome.” Cochrane Library. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

“Information for Healthcare Professionals Methadone Hydrochloride Text Version.” (Nov. 2006). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.

Vicens, C.; Fiol, F.; Llobera, J.; Campoamor, F.; Mateu, C.; Alegret, S.; Socias, I. (Dec. 1, 2006). “Withdrawal from Long-Term Benzodiazepine[…]l in Family Practice.” The British Journal of General Practice. Accessed Feb. 26, 2015.